NYC Community School Boards

Dispatch from New York City

If proportional representation happened in the nation’s largest city, and no one heard it, would it still make a sound?

On April 30, 1969, New York state passed a new decentralization bill that gave the city the elected school boards. And while this story is not about what the NYC Community School Boards accomplished, or weren’t able to accomplish, it’s a story about how the community was better represented by changing their electoral system.

The school boards represented 32 communities throughout one the most diverse cities in the world. The board themselves oversaw elementary and middle schools. Even more, these schools were to represent the parents who likely participated in protests in 1964 that decried deplorable school conditions. In a sense, these school board were to represent not only the demographics of NYC but they were also to represent the diversity of thoughts, dreams, hopes, and ambitions of parents and community members who wanted and worked for a better school system for their children.

The New York City School Boards adopted Proportional Representation. And it’s this electoral system that should be of importance to racial justice advocates and electoral reformers alike.

The proportional representation electoral system used the single-transferrable vote, ranked choice voting, and multi-member districts to elect board members. While this might sound complicated, it was used for 30 years and the results were easily understood: equitable representation.

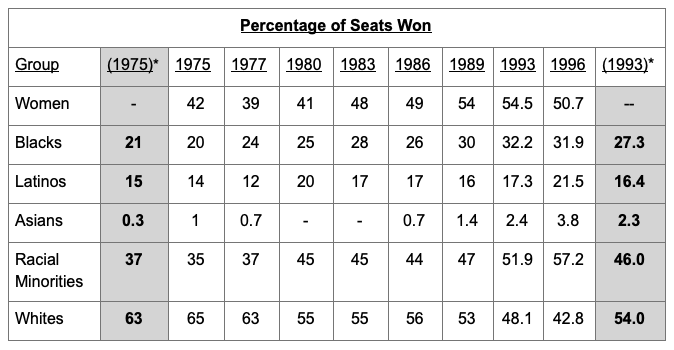

This electoral system resulted in a truly reflective legislative body for Black, white, and brown communities alike. For example, Blacks and Latinos won 38% of school board seats on average while making up about 29% of the NYC voting age population during this time. This kind of representation was not typical, especially compared to the NYC City Council during the same period.

For example, Black and brown communities held 38% of school board seats but held about 5% of the seats on the New York City Council on average during the coinciding three decades. How could the results be so different?

When the community boards adopted PR, they also rejected the NYC City Council’s electoral system: winner-take-all. The architects of the school boards and its electoral system, understood, and quite rightly, that had they adopted the NYC Council’s “winner-take-all” electoral system, thousands of voters would have been left without meaningful representation. It would have also forced them to create racially divided districts to create something only slightly resembling equitable representation. The winner-take-all system could not, and would not, create a school board that looked like and held the same beliefs as the communities they were designed to serve.

Alternatives to Race-Based Districting

Voting Rights enforcement remains as vital, and contentious, as ever. Interest in proportional systems that provide an effective alternative to race-based districting is growing, but only to the extent that the one central question can be confidently answered: are they an effective means to represent the interests of communities of color? Especially in jurisdictions, so common today, with diverse “multiple minority” communities?

The data from Community School Board elections says, “YES!,” especially in light of the backstory. PR easily created meaningful representation for black, white, and brown communities without having to draw district lines based on race.

Equally important, in a Voting Rights “preclearance” review, the U.S. Department of Justice denied an attempt by New York to substitute a less representative election alternative.

Formally, the Community School Boards adopted a form of PR that is known as the Single Transferable Vote. This is a form of ranked choice voting that is used to fairly elect multiple representatives in a single election while ensuring majority rule. PR is designed to facilitate minority representation, while winner-take-all systems inherently limit the range of people, perspectives, and ideas.

NYC City Council Used PR in 1937

It was not PR’s first rodeo in the Big Apple. The mid-20th century history of proportional representation elections in U.S. cities is well-known: a reform movement that broke up oppressive political machines, empowered voters, elected vibrant and diverse City Councils, but ultimately fell under a toxic mix of cold-war bias and racism.

New York City’s adoption of PR in 1937 led to many more elsewhere; unfortunately, after what has been called the “Golden Age” of the New York City Council, so did New York’s shameful red-baiting repeal of PR, and by 1960, only Cambridge Massachusetts remained – now celebrating 80 years of diverse representation in which all voices are fairly heard.

NYC School Boards Faced Steep Challenges but Triumphed

No one described the New York City Community School Board elections in terms even approaching “golden.” The Boards themselves were consistently under siege – sometimes, the election system that represented their best chance at legitimacy occasionally became the target.

Marked by an inadequate election administration infrastructure, abysmal outreach and voter education, severed from all other city elections, the Board elections struggled for air from the outset.

But despite these challenges, PR truly represented voters, in this most diverse of American cities. Effective representation of minority interests is not just about numbers, but it rests on numbers.

Representation under PR is “proportional” to votes won, not to population, but numbers approximating population are a sign of a healthy and accessible democracy while accurately reflecting voter preferences.

PR does not promote or require polarized voting, but if voters are polarized – and evidence submitted to the Justice Department revealed that they often were polarized in these particular elections, between whites and people of color, and even between different communities of color – then PR was there to help sort voter preferences out fairly.

The following summary was prepared prior to the last elections held in May of 1999 (*population share, New York City). Each board had nine members, making the effective threshold to elect one representative 10% of all votes cast.

A Closer Look at PR Election Results in 1996

With separate community boards sprawled across this city of millions, it’s also important to focus on what was happening in the 32 individual districts. The following data was prepared after the May 1996 elections.

Black Representation

In 1996, black candidates were elected in proportion to black voting age population in 26 of 32 districts, down from 28 of 32 districts in 1993. Black candidates also won in 26 districts. Three school boards are one black representative short of proportionate representation; two boards are two representatives short. Citywide, blacks represented far above their share of the voting-age population.

Asian Representation

Asians were elected in proportion to their voting age population in 30 of 32 districts in 1996, as was true in 1993. Asian voters do not make up 20% of voting age population in any school district in the city, yet Asians have at least one seat in 7 districts and 11 of 15 Asian candidates won.

Latinos

In 1996 Latino candidates were elected in proportion to their voting-age population in 18 of 32 districts, up from 13 of 32 districts in 1993. Latinos were under-represented by only one seat on 12 of the 14 school boards where they do not have proportionate representation. They were two representatives short in the other two districts. Latinos had at least one seat in 16 districts, more than one seat in 12 districts and had at least one seat in districts that were at least 16% Latino in every district except District 24.

Whites

Whites won at least a proportionate share of seats in 29 of 32 districts in 1996. Overall, whites were 47.4% of the voting age population and 48.1% of the school boards.

Conclusion

The story of the NYC School Boards is a story that unfolds on the backdrop of social and civil strife for a better world for community members, their families, and their neighbors. The adoption of PR a means to achieve equitable representation became an ends in and of itself.

All told, African-Americans and Latinos won 38% of school board seats in 1996, while constituting just 29% of the New York City’s voting-age population at the time. When we compare these same demographics on the New York City’s Council, we see these two groups held only 5% of seats on the New York City Council. There would have been no good reason to deny themselves representation.

It’s also no wonder that in 1999 the Department of Justice slammed the door shut on New York’s request to move from PR’s single transferable vote to Limited Voting, allowing each voter four votes, while still electing nine. Besides raising the election threshold from 10% to a prohibitive 31%, the city’s own simulations provided evidence of negative impact on minority representation.

The city’s argument that they could then use their voting machines instead of the laborious hand-count was also not persuasive, since proven computerization tools for ranked-ballot elections already existed.

It was apparent that New York needed to boost the profile of the elections themselves, and address deficiencies in its own election administration, and improve education for poll workers and voters alike, rather than risk representation of diverse viewpoints and people for its own convenience. What’s not apparent at first glance is that electoral reform likely should have been a community centered initiative rather than a reform that was issued by the state of New York.

This historical use of proportional representation demonstrates that electoral systems can create fair representation on legislative bodies. Juxtaposed to NYC City Council demographics and their use of “winner-take-all” electoral systems shows how powerful this system can be for liberty, justice, and democracy.